Solid board table and bench

Custom walnut plank dining set with raw edges, LED lighting, glass inserts and metal legs.

Working on the table was a lot of fun. My customer’s order was special (and interesting). And as an incentive - the budget. Her request included the following items:

I tried to document every step of the process, but the deadlines were quite tight and sometimes I didn't have the opportunity to take a photo. Sorry for the missing photos; I will try to describe these steps in more detail...

I don’t consider this stage to be the main one, but it can last quite a long time.Much time, energy and gasoline were spent visiting various sawmills and wood yards in search of suitable material. This seemed like quite a feat considering the width requirements. I needed to find two boards with raw edges, and, placing them side by side, the total width should be the required 100 cm. Their shape should create voids to accommodate the customer’s collection of agates. The boards must have characteristic, pronounced patterns. There were also standard requirements: the boards were dried in an oven or for a couple of years in the air, they had a pleasant appearance, were flat without unnecessary twisting, warping, or cuts (anything that would require removing a layer of thickness). And, of course, the cost must be reasonable.

The search usually begins with electronic classifieds sites in the “building materials” section. Often local craftsmen offer excess boards for sale at reasonable prices. Stores can also post advertisements in an attempt to attract more customers. I found a few decent options nearby, but nothing that fit the bill. Afterwards I visited some local lumberjacks who were sawing logs into planks. These guys often have their own sawmills and sell the board for a good price because they get the logs cheap or free and the quality isn't always the highest. But this option didn’t work either, so I had to move on to stores and warehouses. Obviously, there is already a choice here, but at a very high price.

I finally found what I needed at a local store. Not exactly in the store. It turned out that its owner has his own sawmill and a warehouse full of boards with unedged edges.He had several stacks of nuts from which to choose. Here I found what I was looking for. The boards were the perfect width, cut from the same log (symmetry was maintained), dried in the right conditions for 3 years, nice and flat, and the price was relatively inexpensive. They came with a bonus. Since they were processed with a wide plane, I did not need to sand the unevenly cut surface. I don't have a 60 cm wide plane...

During the search, I sent photos to the client to get her approval. We both decided on these two. Finally the next stage of the project could begin!

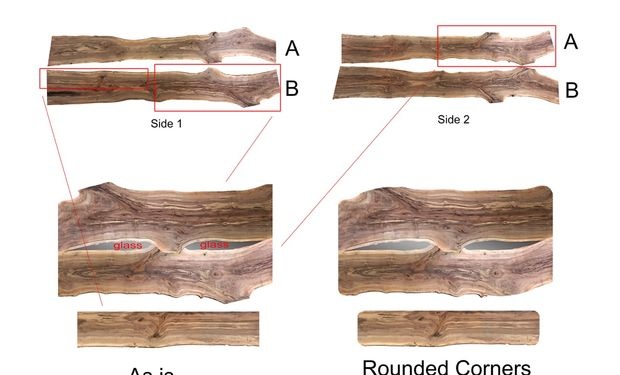

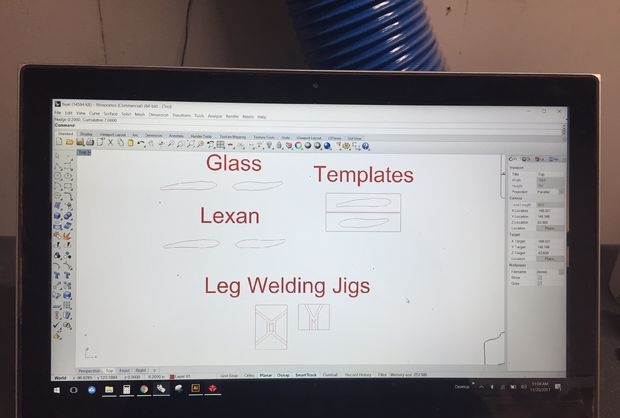

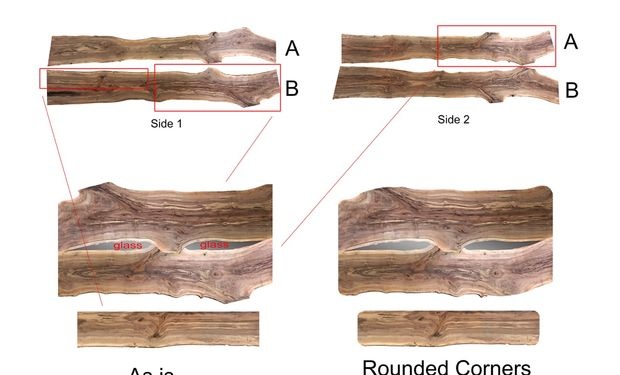

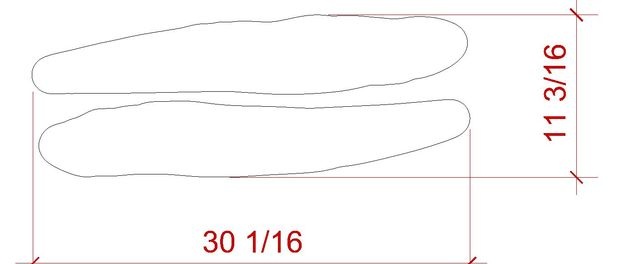

Before I pick up a tool, almost every project I do starts with a computer-aided design (CAD) design. This is a little more difficult to do with raw edges as they are difficult to replicate in CAD. I solved the problem by installing a high ladder and taking photos of the boards along the entire length. Then I imported the pictures into the program and traced the contours. The measuring tape was visible in the photo to help scale the graphics more accurately.

After designing the electronic models, I overlaid them with a real photograph of the surface of the boards so that it would be easier for the customer to imagine what I was going to do. Once we decided on the design, I designed the different elements and how they would interact and attach to each other.

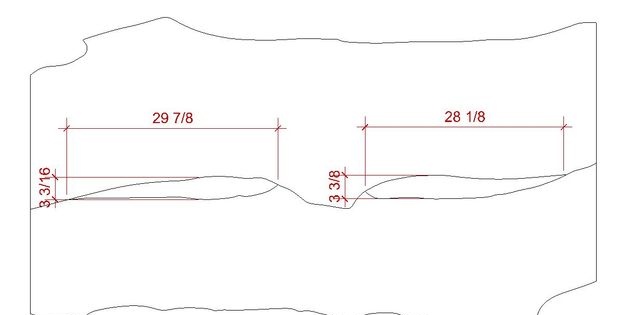

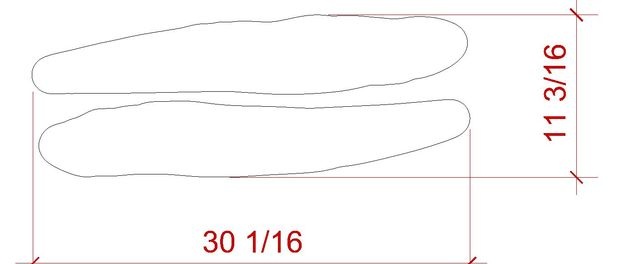

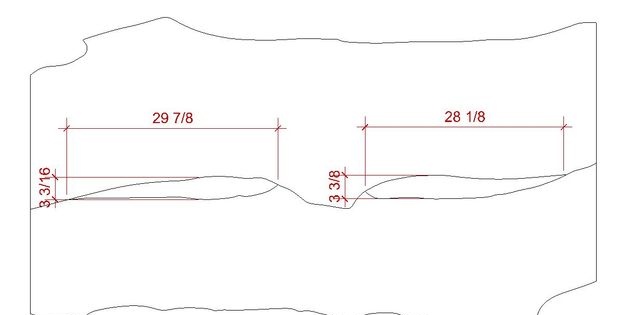

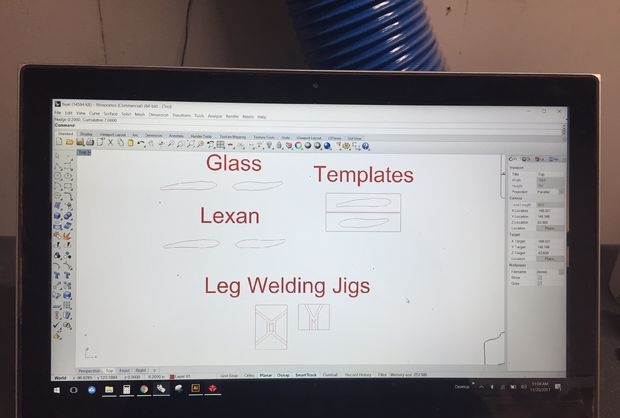

For this project I vectorized different projections of the model for all sorts of purposes. I drew the outlines of the central cavities and exported them to a DXF file, which I then sent to a glass company to have them cut out the same shapes for me.I used the same file to make a template with the outline of the cavity, according to which it will be possible to cut out the polycarbonate plates that will be attached to the underside of the tabletop. I cut the templates and polycarbonate on my homemade CNC router. I also cut out a template to hold the metal leg pieces in place so I could weld them properly. I even laser cut profiles of various metal parts that will help me cut the leg parts at the correct angle. Having designed a complete model in CAD, you can start working, or at least it will be much easier to work with.

In most cases I like to have all the knots, cracks, and voids sealed and filled with black epoxy, especially when working with walnut. Black color most often looks natural, and sometimes adds contrast. Since there were quite deep cracks here and there in the boards, I used a resin with a long curing time; this will allow it to soak in well and help really seal the cracks rather than create the illusion of filling. The disadvantage of this method is that you almost always have to reapply the resin a second, and sometimes a third time. Sometimes I use a resin with a fast cure time for refinishing. I filled in all the voids on both sides of the boards so they could be held securely in place. It is better to apply the epoxy resin in a “heap” so that no bubbles are found during sanding (so they will rise above the plane of the board).

After filling all the voids, I sanded down the exposed parts of the epoxy with a P60 grit abrasive.

Unfortunately, I didn’t really document this stage. Essentially, I laid one board on top of another in the desired position, and marked out the area to be removed. For the actual work, I used a jigsaw, an angle grinder (with a cutter disc and a flap disc), and, where necessary, hand tools for wood carving. There was a lot of fine work and adjustment at this stage. I left a seam approximately 4 millimeters thick along the entire length between the boards. I thought the table would look more expressive this way. On the downside, a seamless fit leaves corners, which is not a good look. The thickness of the seam will be maintained thanks to the dovetail key. I then smoothed out the edges of the table using a circular saw.

During this step, I scraped the raw edges clear of any remaining bark on both the table and bench. I then went over them with an angle grinder with a flap disc to get the rough edges smoother.

On the bench I cut one raw side with a circular saw. I agreed with the customer that the bench would have one side straight.

I used dowels to connect the central parts. They serve to fix two boards in the same plane (relative to each other). The main load of fixing the tabletop will fall on the dowels and legs of the table. Unlike the dowels that I have seen, I made these ones with a thickness almost equal to the thickness of the boards.

The material for the dowels was made by gluing a sheet of walnut between two sheets of mahogany and a CNC machine cut out the shape. I also made a template to help you cut out the dowel slots using a hand router.

After aligning the seam between the boards, I secured them to the table using clamps. Then, using a template, I cut out the grooves with a router. Where the router left the groove round, I had to work with a chisel. You could have done a rounded dovetail, but I like the look of even corners.

Once the dovetail slots were ready, I carefully tried inserting the dovetail (to make sure it wouldn't get stuck!) and started gluing. The dowels were made a little thicker than the grooves, so they were sanded flush with the tabletop.

After this step was completed, I sanded all surfaces going from P60 to P180 grit. A final sanding with P220 grit was carried out immediately before polishing.

I used the CAD model to create the glass inserts and polycarbonate plate. Double-sided tape is perfect for temporarily fixing workpieces on the table surface. I then used the hand router again to create the grooves on both sides of the boards. For more precise work, I used a chisel and a chisel until the glass lay flat and fixed without wobbling. The glass was removed and inserted many times, for this I used suction cups.

The polycarbonate sheet inserts were prepared using a CNC machine and an end mill. Here I had to make a decision on how to more securely secure the plastic inserts to the bottom of the tabletop. I wanted them to be easy to remove, for example to replace them due to scratches. I decided that walnut locking flags would be just right. So I laser cut them out of the material I had.

Before inserting the plastic, I needed to figure out the LED lighting. For a more sophisticated effect, I decided to place LED lighting around the perimeter of the plastic. This technique will also help hide the wires. I purchased a thin LED strip with an adhesive side that can easily be adhered to the indentation I made earlier around the bottom of the cavity. I had to build two separate Y-shaped electrical circuits that would then feed into a separate dimmer. The dimmer is connected to the battery on one side and to a 12-volt power supply on the other. This allows the lamps to glow both from batteries and from the mains. The idea is for homeowners to plug in the charger when they're not using the desk, so the cords can be tucked away when they get in the way. The wires and battery were secured to the bottom of the tabletop using clamps and anchors. I considered the option of embedding the battery and wires into the tree, but finally decided that it was better not to, since all these components will have to be replaced at some point. At the end of the day, this table should be a heirloom that will outlive me, the client, and the LED lights. They say that LED lamps can last quite a long time, but if the desire arises, they can be replaced with something similar.

After trying on the plastic and checking the lighting, I put the plates aside. Locking flags and plastic can be attached after polishing.

The customer wanted to use a polishing material that would preserve the natural appearance of the wood, make it durable, but not look like varnish. So I settled on OSMO PolyX. This product is designed for wooden floors, but also for furniture it fits well.It has a low VOC content and a high solid content as it is primarily composed of waxes and natural oils. It is easy to apply. To achieve a good result, two layers are enough.

I didn't take any photos of this process because I was always wearing rubber gloves covered in polishing paste. Before adding layers, I went over the surfaces and edges again with a P220 grit.

I used a spatula to evenly apply OSMO to the surface. It was easy for them to completely moisten the wood and cover all the small irregularities with the paste. I had to use fabric on the edges. After moistening, I removed the remaining paste with a lint-free cloth. At this stage, it is important to thoroughly work the surfaces, but completely remove the excess. I coated the top, bottom and all the edges of the table and bench and let them dry for a day or two, then did it all over again. Only two coats are enough, and in fact, applying more can result in an undesirable glossy effect.

As a result, the processing of the wooden parts was completed, I laid the polycarbonate plates in place and secured them with flag clamps.

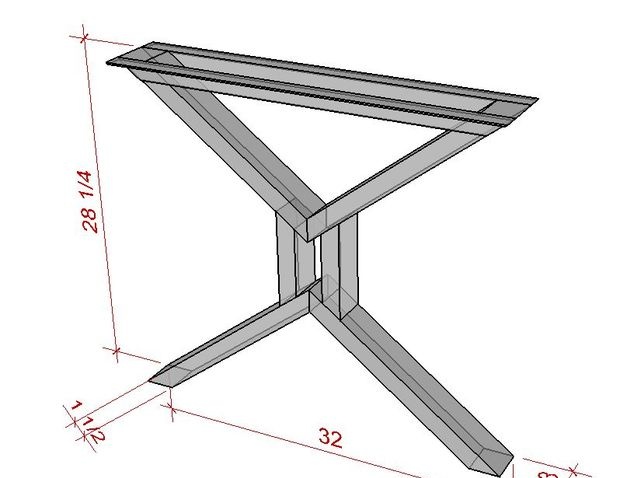

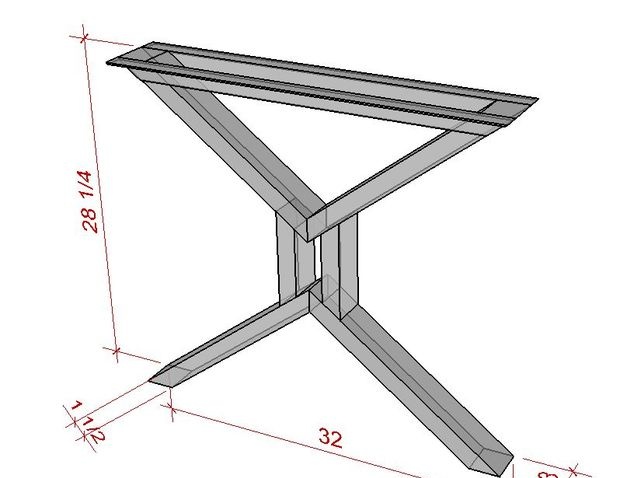

The legs were made from a rectangular steel pipe measuring 3.8 x 7.6 cm and a 3.8 x 3.8 cm iron angle. To make the process easier, I used a laser cutter to cut out templates to hold the necessary components in place and a blank to help put everything together at the correct angle. A long time ago I was an excellent welder, but years passed and without sufficient practice I still had functional skills, but I forgot how to weld with decorative seams.To smooth out this imperfection, I used an angle grinder to grind off the excess metal and give the surface a cleaner look.

Once the welding was complete, I sanded all the metal surfaces with an angle grinder and a flap disc to ensure they had a uniform texture and shine. I cut oblong holes in the angle metal to attach the tabletop to, so that if the wood contracts or expands there won't be any problems. I welded the lower parts of the legs with iron plates, so that I could then drill holes in them and install the height adjustment mechanism.

The customer wanted the legs to be black. We thought a little about how best to do this. Instead of paint, we decided to use a steel bluing agent, so the result will be more durable and will better hide imperfections. I used a product called presto black. Application was carried out through a spray bottle until all surfaces were covered with the substance, and then its effect was neutralized with a solution of baking soda so that the metal did not begin to oxidize (rust). After removing the bluing agent, I dried the metal with a compressor and coated the surface with matte polyurethane to prevent it from rusting along the way.

I used furniture nuts and bolts to attach the legs, which will allow the legs to be removed and installed over and over again. I secured the legs of the bench with large wood screws, since it is not large and can be moved without removing the legs.

The customer lives three hours away from me, so when transporting the table it was important to pack it correctly. I removed the legs from the bench and table and wrapped each component separately and sealed it in plastic packing material.It is important to wrap and pack the parts in the order they are disassembled so that when you put them back together they will be in the correct order. It will be easier. For example, when I arrived at a client's house, the first thing I had to unload from the van was the countertop. I placed it upside down on the floor in the house. The next pieces available were the legs, which I attached to the tabletop. Then the bench, the legs of the bench and so on. This may seem like common sense, but when you get carried away with packing, it's easy to forget about everything. I didn’t film this process, but I’m sure it’s pretty easy to imagine.

The customer really liked the dining set, and now her collection of agates lies in the illuminated recesses, in the middle there is a bouquet for the season, and around there is a specially selected set of chairs. It's in the photo. A table can add some life to an already cute room. I am glad that this creation will go to a beautiful home where it will be admired and cared for.

Thank you for your attention!

Original article in English

Working on the table was a lot of fun. My customer’s order was special (and interesting). And as an incentive - the budget. Her request included the following items:

- - Tabletop with uncut edges on both sides, consisting of two separate walnut boards.

- - Lots of patterns and contrast.

- - Cavities in the middle for agate collection.

- - To illuminate the agates, there must be LED lighting in the cavity.

- - The cavities are covered with removable glass inserts.

- - Tabletop dimensions 100 cm wide and 210 cm long.

- - Custom made steel legs (blacked out).

- - One bench in a similar style.

- - Production time is no more than a month.

I tried to document every step of the process, but the deadlines were quite tight and sometimes I didn't have the opportunity to take a photo. Sorry for the missing photos; I will try to describe these steps in more detail...

Search for material

I don’t consider this stage to be the main one, but it can last quite a long time.Much time, energy and gasoline were spent visiting various sawmills and wood yards in search of suitable material. This seemed like quite a feat considering the width requirements. I needed to find two boards with raw edges, and, placing them side by side, the total width should be the required 100 cm. Their shape should create voids to accommodate the customer’s collection of agates. The boards must have characteristic, pronounced patterns. There were also standard requirements: the boards were dried in an oven or for a couple of years in the air, they had a pleasant appearance, were flat without unnecessary twisting, warping, or cuts (anything that would require removing a layer of thickness). And, of course, the cost must be reasonable.

The search usually begins with electronic classifieds sites in the “building materials” section. Often local craftsmen offer excess boards for sale at reasonable prices. Stores can also post advertisements in an attempt to attract more customers. I found a few decent options nearby, but nothing that fit the bill. Afterwards I visited some local lumberjacks who were sawing logs into planks. These guys often have their own sawmills and sell the board for a good price because they get the logs cheap or free and the quality isn't always the highest. But this option didn’t work either, so I had to move on to stores and warehouses. Obviously, there is already a choice here, but at a very high price.

I finally found what I needed at a local store. Not exactly in the store. It turned out that its owner has his own sawmill and a warehouse full of boards with unedged edges.He had several stacks of nuts from which to choose. Here I found what I was looking for. The boards were the perfect width, cut from the same log (symmetry was maintained), dried in the right conditions for 3 years, nice and flat, and the price was relatively inexpensive. They came with a bonus. Since they were processed with a wide plane, I did not need to sand the unevenly cut surface. I don't have a 60 cm wide plane...

During the search, I sent photos to the client to get her approval. We both decided on these two. Finally the next stage of the project could begin!

Design development and approval

Before I pick up a tool, almost every project I do starts with a computer-aided design (CAD) design. This is a little more difficult to do with raw edges as they are difficult to replicate in CAD. I solved the problem by installing a high ladder and taking photos of the boards along the entire length. Then I imported the pictures into the program and traced the contours. The measuring tape was visible in the photo to help scale the graphics more accurately.

After designing the electronic models, I overlaid them with a real photograph of the surface of the boards so that it would be easier for the customer to imagine what I was going to do. Once we decided on the design, I designed the different elements and how they would interact and attach to each other.

For this project I vectorized different projections of the model for all sorts of purposes. I drew the outlines of the central cavities and exported them to a DXF file, which I then sent to a glass company to have them cut out the same shapes for me.I used the same file to make a template with the outline of the cavity, according to which it will be possible to cut out the polycarbonate plates that will be attached to the underside of the tabletop. I cut the templates and polycarbonate on my homemade CNC router. I also cut out a template to hold the metal leg pieces in place so I could weld them properly. I even laser cut profiles of various metal parts that will help me cut the leg parts at the correct angle. Having designed a complete model in CAD, you can start working, or at least it will be much easier to work with.

Preparation of boards (filling cracks, fixing knots, sanding)

In most cases I like to have all the knots, cracks, and voids sealed and filled with black epoxy, especially when working with walnut. Black color most often looks natural, and sometimes adds contrast. Since there were quite deep cracks here and there in the boards, I used a resin with a long curing time; this will allow it to soak in well and help really seal the cracks rather than create the illusion of filling. The disadvantage of this method is that you almost always have to reapply the resin a second, and sometimes a third time. Sometimes I use a resin with a fast cure time for refinishing. I filled in all the voids on both sides of the boards so they could be held securely in place. It is better to apply the epoxy resin in a “heap” so that no bubbles are found during sanding (so they will rise above the plane of the board).

After filling all the voids, I sanded down the exposed parts of the epoxy with a P60 grit abrasive.

Shaping joints

Unfortunately, I didn’t really document this stage. Essentially, I laid one board on top of another in the desired position, and marked out the area to be removed. For the actual work, I used a jigsaw, an angle grinder (with a cutter disc and a flap disc), and, where necessary, hand tools for wood carving. There was a lot of fine work and adjustment at this stage. I left a seam approximately 4 millimeters thick along the entire length between the boards. I thought the table would look more expressive this way. On the downside, a seamless fit leaves corners, which is not a good look. The thickness of the seam will be maintained thanks to the dovetail key. I then smoothed out the edges of the table using a circular saw.

During this step, I scraped the raw edges clear of any remaining bark on both the table and bench. I then went over them with an angle grinder with a flap disc to get the rough edges smoother.

On the bench I cut one raw side with a circular saw. I agreed with the customer that the bench would have one side straight.

Connecting boards using dowels and dowels

I used dowels to connect the central parts. They serve to fix two boards in the same plane (relative to each other). The main load of fixing the tabletop will fall on the dowels and legs of the table. Unlike the dowels that I have seen, I made these ones with a thickness almost equal to the thickness of the boards.

The material for the dowels was made by gluing a sheet of walnut between two sheets of mahogany and a CNC machine cut out the shape. I also made a template to help you cut out the dowel slots using a hand router.

After aligning the seam between the boards, I secured them to the table using clamps. Then, using a template, I cut out the grooves with a router. Where the router left the groove round, I had to work with a chisel. You could have done a rounded dovetail, but I like the look of even corners.

Once the dovetail slots were ready, I carefully tried inserting the dovetail (to make sure it wouldn't get stuck!) and started gluing. The dowels were made a little thicker than the grooves, so they were sanded flush with the tabletop.

After this step was completed, I sanded all surfaces going from P60 to P180 grit. A final sanding with P220 grit was carried out immediately before polishing.

Insertion of glass, polycarbonate and LED lighting

I used the CAD model to create the glass inserts and polycarbonate plate. Double-sided tape is perfect for temporarily fixing workpieces on the table surface. I then used the hand router again to create the grooves on both sides of the boards. For more precise work, I used a chisel and a chisel until the glass lay flat and fixed without wobbling. The glass was removed and inserted many times, for this I used suction cups.

The polycarbonate sheet inserts were prepared using a CNC machine and an end mill. Here I had to make a decision on how to more securely secure the plastic inserts to the bottom of the tabletop. I wanted them to be easy to remove, for example to replace them due to scratches. I decided that walnut locking flags would be just right. So I laser cut them out of the material I had.

Before inserting the plastic, I needed to figure out the LED lighting. For a more sophisticated effect, I decided to place LED lighting around the perimeter of the plastic. This technique will also help hide the wires. I purchased a thin LED strip with an adhesive side that can easily be adhered to the indentation I made earlier around the bottom of the cavity. I had to build two separate Y-shaped electrical circuits that would then feed into a separate dimmer. The dimmer is connected to the battery on one side and to a 12-volt power supply on the other. This allows the lamps to glow both from batteries and from the mains. The idea is for homeowners to plug in the charger when they're not using the desk, so the cords can be tucked away when they get in the way. The wires and battery were secured to the bottom of the tabletop using clamps and anchors. I considered the option of embedding the battery and wires into the tree, but finally decided that it was better not to, since all these components will have to be replaced at some point. At the end of the day, this table should be a heirloom that will outlive me, the client, and the LED lights. They say that LED lamps can last quite a long time, but if the desire arises, they can be replaced with something similar.

After trying on the plastic and checking the lighting, I put the plates aside. Locking flags and plastic can be attached after polishing.

Polishing

The customer wanted to use a polishing material that would preserve the natural appearance of the wood, make it durable, but not look like varnish. So I settled on OSMO PolyX. This product is designed for wooden floors, but also for furniture it fits well.It has a low VOC content and a high solid content as it is primarily composed of waxes and natural oils. It is easy to apply. To achieve a good result, two layers are enough.

I didn't take any photos of this process because I was always wearing rubber gloves covered in polishing paste. Before adding layers, I went over the surfaces and edges again with a P220 grit.

I used a spatula to evenly apply OSMO to the surface. It was easy for them to completely moisten the wood and cover all the small irregularities with the paste. I had to use fabric on the edges. After moistening, I removed the remaining paste with a lint-free cloth. At this stage, it is important to thoroughly work the surfaces, but completely remove the excess. I coated the top, bottom and all the edges of the table and bench and let them dry for a day or two, then did it all over again. Only two coats are enough, and in fact, applying more can result in an undesirable glossy effect.

As a result, the processing of the wooden parts was completed, I laid the polycarbonate plates in place and secured them with flag clamps.

Creating legs and installing them

The legs were made from a rectangular steel pipe measuring 3.8 x 7.6 cm and a 3.8 x 3.8 cm iron angle. To make the process easier, I used a laser cutter to cut out templates to hold the necessary components in place and a blank to help put everything together at the correct angle. A long time ago I was an excellent welder, but years passed and without sufficient practice I still had functional skills, but I forgot how to weld with decorative seams.To smooth out this imperfection, I used an angle grinder to grind off the excess metal and give the surface a cleaner look.

Once the welding was complete, I sanded all the metal surfaces with an angle grinder and a flap disc to ensure they had a uniform texture and shine. I cut oblong holes in the angle metal to attach the tabletop to, so that if the wood contracts or expands there won't be any problems. I welded the lower parts of the legs with iron plates, so that I could then drill holes in them and install the height adjustment mechanism.

The customer wanted the legs to be black. We thought a little about how best to do this. Instead of paint, we decided to use a steel bluing agent, so the result will be more durable and will better hide imperfections. I used a product called presto black. Application was carried out through a spray bottle until all surfaces were covered with the substance, and then its effect was neutralized with a solution of baking soda so that the metal did not begin to oxidize (rust). After removing the bluing agent, I dried the metal with a compressor and coated the surface with matte polyurethane to prevent it from rusting along the way.

I used furniture nuts and bolts to attach the legs, which will allow the legs to be removed and installed over and over again. I secured the legs of the bench with large wood screws, since it is not large and can be moved without removing the legs.

Delivery and installation

The customer lives three hours away from me, so when transporting the table it was important to pack it correctly. I removed the legs from the bench and table and wrapped each component separately and sealed it in plastic packing material.It is important to wrap and pack the parts in the order they are disassembled so that when you put them back together they will be in the correct order. It will be easier. For example, when I arrived at a client's house, the first thing I had to unload from the van was the countertop. I placed it upside down on the floor in the house. The next pieces available were the legs, which I attached to the tabletop. Then the bench, the legs of the bench and so on. This may seem like common sense, but when you get carried away with packing, it's easy to forget about everything. I didn’t film this process, but I’m sure it’s pretty easy to imagine.

The customer really liked the dining set, and now her collection of agates lies in the illuminated recesses, in the middle there is a bouquet for the season, and around there is a specially selected set of chairs. It's in the photo. A table can add some life to an already cute room. I am glad that this creation will go to a beautiful home where it will be admired and cared for.

Thank you for your attention!

Original article in English

Similar master classes

Particularly interesting

Comments (1)